For many of us, we may wonder why gasoline is labeled as unleaded as it’s been banned for use in automobiles since 1975. But leaded gasoline is still allowed for aircraft, racing cars, farm equipment, and marine engines, it’s been banned for use in automobiles since 1975.

And it was this week in 1985 that the Environmental Protection Agency announced it was considering a total ban on leaded gasoline by 1988, due to the adverse effects on human health, a ban still in effect.

The move came as a 1985 EPA study estimated that as many as 5,000 Americans died annually from lead-related heart disease. But as we consider the effects of burning gasoline at all, with governments looking to ban the use of gasoline in internal combustion engines, it’s interesting to look back at a time when the government wasn’t concerned about the effects of burning leaded gasoline, even though it was never needed.

Looking to profitably solve a problem

The quality of gasoline in the early 20th century wasn’t very good, and engine knock was common. Unknown to most drivers today, engine knock was a common malady in early motoring, occurring when fuel prematurely ignites in an engine cylinder. Not only does this reduce efficiency, it also can lead to engine damage.

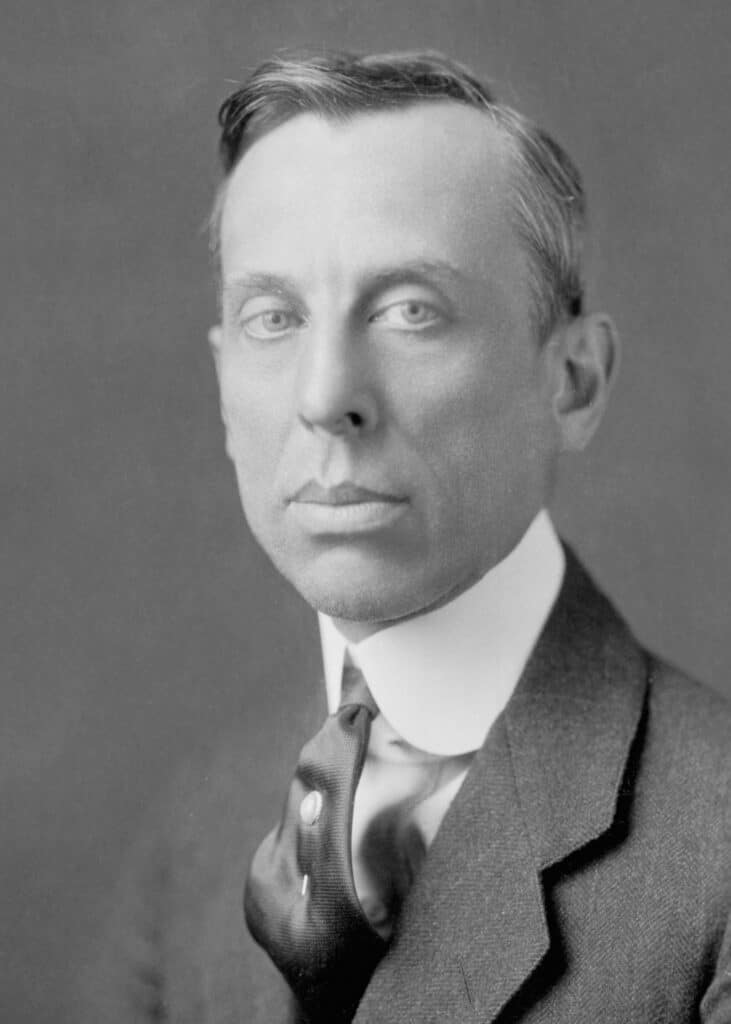

It was a problem well known to automakers, including General Motors and one of its employees: chemist Thomas Midgley Jr.

Born in 1889 in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, Midgely earned a degree in mechanical engineering from Cornell University, before joining the National Cash Register Company in Dayton, Ohio. By 1916, he was working for Charles Kettering at the Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company (Delco), and would be on staff when it became GM’s research division in 1919.

Nevertheless, Midgely had been working on the problem of engine knock since 1916, trying any number of substances before finding that ethanol would quell engine knock. But from the perspective of General Motors, it was problematic, if only for one reason: it couldn’t be patented, and so its production couldn’t be controlled by GM. And oil companies didn’t like it since it could replace gasoline as a fuel for internal combustion engine.

A toxic solution

So, by 1921, Midgely discovered that adding diminutive amounts of highly-toxic tetraethyl lead, or TEL, to gasoline, completely eliminated engine knock. But it was known to be a poison for centuries, one that DuPont said at the time was, “very poisonous if absorbed through the skin, resulting in lead poisoning almost immediately.”

Yet in 1922, General Motors Corp., the DuPont Co., and the Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey (now known as Exxon) formed the Ethyl Gasoline Corp. to knowingly produce and distribute carcinogen- laden leaded gasoline.

Brothers Pierre and Irénée du Pont had major investments in GM, and stood to profit handsomely from sales of poisonous Ethyl gasoline through their new joint venture. And Midgley won the 1923 Nichols Medal in 1922 from the American Chemical Society for his discovery.

By the time the first tankful was sold the following year, Midgely was in bed with lead poisoning, although he survived. Others weren’t so lucky. By 1924, 15 Ethyl Corp. workers died from lead poisoning. It would be decades of hiding the truth by both the government and corporations about the effects of leaded gasoline in poisoning both humans and the environment before the truth would come to light.

A troubling, toxic legacy

Ethyl Gasoline Corp. was sold to Albemarle Paper in 1962 which, once leaded gasoline was banned, continued to sell it in third world countries, as well as for other uses where it’s allowed.

Lead is a neurotoxin, one that doesn’t break down. But since lead particles travel in the wind, the poisoning continues, albeit on a smaller scale. So, the estimated seven million tons of lead burned in gasoline remains with us long after the fuel has been burned. It still resides in the land, air and water exposing us at levels estimated to be 500 times greater than natural levels, with 90% coming from the burning of gasoline.

As for the man who permanently polluted the earth, Midgely would add to his own toxic legacy.

In 1930, he was tasked with finding a refrigerant gas for use in freezers and air conditioners that was odorless, nontoxic, and nonflammable. He settled on dichlorodifluoromethane, also known as Freon-12 or R-12, which actively depletes the ozone layer, which resides 9-to-18 miles above the Earth and absorbs a portion of the radiation from the sun, preventing it from reaching the surface and harming humans, animals and plants.

Nice going Midgely; you’re two-for-two.

In 1940, Midgely contracted polio, becoming unable to walk. He would die in 1944, strangling himself while using a hoist he created to assist in getting in and out of bed. He was 55 years old.

I am completely blown away by this article. As an automotive service shop owner for 50 years and host for 30 years of the Nationally syndicated radio broadcast program, Bobby Likis Car Clinic and rear-engine drag race engine builder, I have promoted ethanol to my many listeners who – at best – wanted to toss me under the bus for stating far less negative points re leaded gasoline. I applaud Larry and The Detroit News for this article. Too little…too late as it is!

This is generally a pretty good article. It’s just a shame that The Detroit Bureau took so long to publish something like this.

A couple of things to point out, Pierre Dupont wasn’t just an investor in GM, he was president when the TEL discovery was made, and then became Chairman of the GM Board when Sloan was put in as president. The Dupont family benefitted doubly by the leaded gasoline patent: As owners of Dupont, the chemical company making the poison, and then as the people who owned the largest share of GM stock.

Midgely, like his assistant Boyd, and boss Kettering actually believed that ethanol would be the ingredient to calm engine knock, and be the fuel of the future. They only became fans of TEL when it was realized how much the patent would be worth.