First came the shortages of masks and hand sanitizer, then tissues and toilet paper. Scarcity became reality during the COVID-19 pandemic. But now, as widespread vaccination frees up millions of Americans to take long-delayed summer vacations, a new shortage is cropping up: a lack of gasoline.

There’s plenty of petroleum at the nation’s refineries, in fact. The real issue is a shortage of drivers to get it to the pump.

Ironically, many tank truck drivers were let go when the pandemic first struck and millions of Americans went into lockdown. Now, up to 25% of U.S. tankers are sitting idle with no one to put behind the wheel.

Pandemic’s petro-rollercoaster

U.S. roadways went eerily silent as much of the country was idled at this time last year. In major metropolitan areas like New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, traffic fell by as much as 80%, according to tracking service Tom Tom. There was such a glut of petroleum that oil tankers often sat at sea, waiting to empty their loads.

That sent gas prices tumbling, some U.S. service stations charging less than a dollar a gallon in spring 2020. Demand has been rising since then and the typical U.S. motorist is paying $2.88 a gallon for regular unleaded today, according to AAA.

But there’s growing concern that prices could surge even more sharply, especially if the country starts to experience gasoline shortages should there not be enough drivers found to get fuel to where it’s needed.

“Trucking’s driver shortage already exceeds 50,000 drivers,” the National Tank Truck Carriers (NTTC), an industry trade group, reported on its website. And that’s only part of the problem, it adds. “The trucking industry’s workforce shortage is not confined to drivers alone. Trucking companies also require dispatchers and back office staff. Trained mechanics are also in short supply. Tank truck operations face further critical shortages of registered inspectors and design-certified engineers who can inspect and repair cargo tank truck trailers.”

Driver shortage grows worse

In recent years, there’s been a growing shortage of truck drivers, in general. The work is demanding, the pay often marginal, especially for those operating their own rigs.

Complicating matters, not everyone licensed to haul an 18-wheeler can operate a tank truck. Beyond the basic commercial license, a driver needs to get additional certification considering the dangerous loads they’ll be hauling.

Then, early last year, a new federal registry debuted. It identified drivers who have had issues with alcohol or drugs. As many as 60,000 of them are no longer available as a result.

Tanker fleet operators struggled with the lack of business last year and are now trying to cope with the driver shortage. When lockdown began and demand for gas plunged, “We were even hauling boxes for Amazon just to keep our drivers busy,” Holly McCormick, vice president in charge of driver recruitment and retention at Oklahoma tanker company, told CNN. “A lot of drivers didn’t want to do the safety protocols. We’re also working with an aging work force. Many said ‘I might as well take it as a cue to retire.'”

Even in normal times, driver turnover can run 50% annually. It hit 70% during the depths of the COVID crisis, Brad Fulton, director of research and analytics at Stay Metrics, told the network.

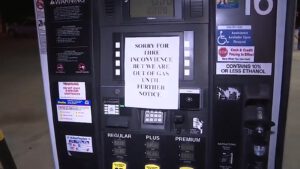

Spot shortages

Schools that train new drivers simply can’t keep up, according to industry insiders. And there are additional roadblocks in the licensing process, argues the NTTC which, in a report on the shortage, said steps are essential for “speeding and easing the CDL (commercial driver’s) licensing process.”

There have already been reports of spot shortages hitting vacation centers like Florida and Arizona during the recent spring break, according to the Oil Price Information Service.

Experts say these could become more widespread during the summer months as more Americans start to travel again — especially with the CDC revising outdoor mask guidelines for those who’ve been fully vaccinated.

The real concern is that even a brief shortage at a handful of stations could cause the same sort of panic that occurred last year when supplies of toilet paper fell short, shoppers lining up at groceries and big box outlets like Costco, snapping up every roll they could find.

If everyone suddenly decides they need a full tank of gas at all times it could strain supplies. It also could lead to long lines of cars waiting to fuel up — bringing back echoes of the gas shortages America faced in the 1970 oil shocks. Except, this time, there’s a plentiful supply of both petroleum, but a shortage of the trucks needed to get fuel where it’s needed.